"It was always my intention

to write this history for folks who were stationed at Tempelhof. I

really can't think of a better way to do that, than to offer it to BIA

for the Newsletter and Web Site. This first part covers the history from

earliest times through to about 1900. The next part will address

the history of aviation and airports at Tempelhof, and although I have

boxes of books and source material, I have not yet started to organize that

information. Therefore, "Part 2" will take a while."

--

Jim Kavanagh (64-70/74-78)

________________________________________________________________________

I cannot tell how the truth may be;

~~~ Tempelhof Field Tempelhof Field is situated in the

northern rim of the Teltow Plateau, overlooking a ford across the River

Spree at present-day Berlin. The location has been strategically

important throughout recorded history. It is at the crossroads of a

direct north-south route from the Lower Oder River and the Baltic to the

Mediterranean, with a major west-east route through Magdeburg and

Brandenburg eastward to Poland and Russia. This same location marked the

boundary between the territories of the major Wend settlements at

Spandau and at Köpenick, and also between the German frontier

territories of Brandenburg and Meissen. Politically,

the region is in the "Mittelmark" or central section of the "Mark"

("March" or frontier territory) Brandenburg, which was called the "Nordmark"

until about the 12th Century. The boundaries of this frontier

territory were drawn during Archeological findings support human presence in

the vicinity from about 8,000 BC, when hunters left evidence of their

passage at a campsite near Tegel. Several Stone Age sites (dated roughly

from 3,000 to 1,800 B.C.) have been found around the periphery of

Tempelhof Field, which reflect the change in lifestyle, during the slow

shift from hunting and gathering to farming and settlement. Shelters

were built more substantial and permanent. Clothing was made from plant

fibers in addition to leather or fur. Family groups started to band

together and specialization appears. Cultural groups became known by the

type of pottery they produced and used. German

influence out of the North was felt in this area from about 2,000 B,C.

Driven largely by overpopulation and severe climate changes, this German

migration accelerated dramatically about 800 B.C., and within the next

300 years, German tribes had forced the Celts and others out of most of

North Central Europe. As German tribes continued to push south, the

resulting confrontation with the "civilized world" gave us our first

look at the Semnones, the people then in the region that would someday

be Tempelhof. Publius Cornelius Tacitus (54 – 120

A.D.) was a Roman Historian who left us a descriptive study of German

life and culture entitled "Germania". Exactly how Tacitus came by this

knowledge is not known. However, Northern Europe was a source for

slaves, amber, furs and animals, and a main trade route to and from that

region passed through the territory of the Semnones. Tacitus would have

known about the Germans, and possibly even knew traders who dealt

directly with them. "Of all the Suevians, the

Semnones recount themselves to be the most ancient and most noble. The

belief of their antiquity is confirmed by religious mysteries. At a

stated time of the year, all of the people descended from the same stock

assemble by their deputies in a wood consecrated by the idolatries of

their forefathers, and by superstitious awe in times of old. There, by

publicly sacrificing a man, they begin the horrible solemnity of their

barbarous worship." Tacitus continues, "The potent condition of the

Semnones has increased their influence and authority, as they inhabit a

hundred towns, and from the largeness of their community it follows,

that they hold themselves for the head of the Suevians."

According to Tacitus, the Suevians were an alliance of four tribes –

Herminones, Langobards, Hermondurians and Marcomanians, and the Semnones

were a branch of the Hermondurians, who were also known as the "Elbgermanen"

(Elbe River Germans). Coming out of the

east-southeast, the Huns overran, defeated or stampeded tribal groups on

their push westward, causing a "domino effect" cascade of migration

before them. The defeat of the Ostrogoths by the Huns in 375 A.D is

generally held to be the start of the Great Migrations westwards. The

last report of the Suevians, dated 568 A.D., has them moving

west-southwest away from the vicinity and places them in the Harz

Mountains. Only a very few German artifacts dated after this have been

found around the periphery of Tempelhof, along with traces of the

passage of the Burgundians through here on their route to the Rhone

Valley. In the next wave of migration, the "Heveller"

established their seat at Spandau and controlled the west, while the "Spreewanen"

settled at Köpenick and held the east. Since Slavic structure is

complex, and names tend to be localized, they are collectively referred

to as "Wends". As with other cultures and periods, no Wend artifacts

have been found either on or in close proximity to Tempelhof Field,

suggesting that it was unsettled, perhaps a buffer zone or shared

hunting ground. The German migration pressured, then

broke Roman borders. They moved in and established their own rule,

adopting or adapting to Roman order, organization, society, and values.

Somewhat later, the Franks, under Charles the Great (also

known as "Charlemagne" or "Karl der Grosse"), achieved supremacy over

this conglomerate of Germanic tribes and groups. Pope Leo III crowned

him "Emperor of the Romans" in 800 A.D. Charles the Great aggressively

pursued territorial expansion, and the conflicts with the Saxons from

roughly 772 to 804 probably helped orient major efforts eastwards. The

other compass directions would have been much less promising – the

Atlantic, the cold north and Northmen or "Vikings", and the densely

populated Mediterranean basin to the South. History

speaks of a "Frisian Corps" moved by boat against the stronghold at

Potsdam in 789 A.D. to punish Wend allies of the Saxons. Excavations at

Spandau uncovered settlements that may have been destroyed by this same

expedition, based on arrow scars and burnt remainders that were found on

the river side of the settlements. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume

that foraging and scouting parties ranged through Tempelhof at that

time, even though no specific archealogical evidence is known.

Charles the Great established the eastern border of his

empire along the Elbe River in 805 A.D., and identified trading posts

and border crossings at Bardowick on the Elbe, Magdeburg and Schezla.

Adventurers, travelers and traders who used these crossings were

undoubtedly the source for the tales of a "land of milk and honey"

beyond the Elbe, with huge stretches of unsettled land free for the

taking. Roughly a century later, Henry I (919-936

A.D.), a Saxon who is credited with founding the German nation, crossed

the Elbe and captured the Wend stronghold at Brandenburg in 928/929 A.D.

Eastward expansion was continued during the reign of his son, Otto I

(936-973 A.D.), who founded the Brandenburg Diocese in 948 A.D. and gave

it a mission territory called the "Gau Zpriawani", which encompassed

territory along both sides of the River Spree from Spandau to Köpenick,

including Tempelhof. Otto invested a nobleman named Gero with this

frontier territory along with the title of "Duke". Gero proved himself

worthy of this recognition by securing territory as far east as the Oder

and Peene Rivers, and forcing the Wends to pay tribute and be baptized.

The East Frontier became the "Wild East" about 983 A.D. when the Wends

rebelled. They overran fortifications and destroyed settlements. During

the ensuing struggle, which lasted nearly 150 years, control of the

frontier reportedly changed hands ten times. Histories show a confusing

mixture of shifting alliances, fighting and infighting between the

Germans, Wends and Poles. Meanwhile, the rest of

Europe was preparing for the Crusades. Pope Urban II issued a call to

arms for Christians to recover the Holy Land. Norman, Flemish and French

knights served in the First Crusade, from 1096 to 1099 A.D., which was

the most successful of all of the Crusades. This success must have been

embarrassing for the Magdeburg Archbishop, since the "Brandenburg

Diocese", the "Havelburg Diocese" and the "Havelburg Mission" were

essentially just names on a map, with the land controlled by the

heathens. The call to arms was not long in coming, for in 1108 A.D. a

proclamation was read at Magdeburg, which said in part:

…"Oppressed by many and unending calamities and acts of violence that we

have had to endure at the hands of the heathen, we implore your mercy,

that you may come to our aid in halting the ruin of your Mother, the

Church. The most cruel of heathen people have risen against us and have

become all-powerful, men without mercy, glorying in their human

malignity. Arise then, Spouse of Christ, and come! Thy voice shall sound

into the ears of the faithful, so that all will speedily join the army

of Christ. These peoples are the most wicked of all, but their land is

the best of all, abounding in meat, honey, and corn. It need only be

cultivated in the right manner to overflow with all the fruits of the

soil" … "Well then, you Saxons, you people of Lorraine, you Flemings,

you renown conquerors of the earth: here is an opportunity not only to

save your souls but, if you wish, also to acquire the finest land as

your dwelling place." A sideline issue of extreme

importance to Tempelhof’s history occurred in 1134 A.D., when Emperor

Lothar invested Albrecht "the Bear" of the Ascanian House with the north

frontier. The Margraves of the Ascanian House, and particularly

Albrecht, were the architects of the Mark Brandenburg, and were directly

responsible for the settlement and cultivation of Tempelhof. This

investiture contained several quirks: "…not only did

Albrecht the Bear come from the "Schwabengau" in Lower Saxony in the

Harz Mountains, into which the "Nordschwaben" were resettled in 568, but

also the majority of the colonists who came into this area along with

others from Lower Franconia, Flanders and "Brabant"."

Thus, descendents of the last of the Suevians to leave the area during

the Great Migration were some of the first colonists to resettle the

region over six hundred years later. The most successful of the

margraves, from the Ascanian and Hohenzollern Houses, were also from the

same stock. The crusade against the Wends was launched

in 1147 and attracted the interest and participation of German, Danish

and Polish noblemen. Although Albrecht the Bear led only one section of

this crusade, he gained the majority of his domain from this conquest.

The Wend prince who controlled a large territory, which included the

Tempelhof area, converted to Christianity and was baptized, and took the

name "Heinrich", thus sparing his territory the effects of the invasion.

The main military operations of the Wend Crusade were

conducted in the northern region and its major accomplishment was the

recovery of the Havelburg Diocese. Although the role played by Poland is

not clear, there are indications that the Poles pushed west as far as

Köpenick. This may have been the reason for Albrecht’s reported trip to

Kruschwitz, where he met Polish nobles on 11 January 1148.

The Wend Crusade served several long term purposes: it gave

interested parties a chance to view the territory, it concentrated

German and European interest eastwards, and it provided the opportunity

for participants to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of their

future competition in the upcoming "land grab".

Albrecht the Bear inherited Brandenburg when Heinrich (the Wend

nobleman) died in 1150, but lost it almost immediately to another

nobleman named Jaxa, who, although he has been identified as both a Wend

and a Pole, is generally believed to have come from Köpenick.

Albrecht the Bear was forced to withdraw. He sought an alliance with

Archbishop Wichmann of Magdeburg, and their combined force took

Brandenburg during the following field campaign. The date of this

victory, 11 June 1157, is regarded as the birth date of the Mark

Brandenburg. Albrecht went on a pilgrimage to

Jerusalem in thanksgiving. He returned in 1159, and within a year the

Ascanians had pushed further east and taken the Wend stronghold at

Spandau. In this same rough timeframe, Albrecht defeated Jaxa in a

battle that reportedly took place near Grossglienicke, and it is Jaxa’s

flight across the Havel that forms the basis for the Shildhorn Legend.

The Ascanians constructed a strongpoint on the site of the present-day

Zitadelle, and Spandau became their residence and main base of

operations. Albrecht is credited with establishing Ascanian military

power. To obtain the necessary troops, he decreed that every ninth man

had to serve, while robbers were given the choice of serving or being

hanged. Magdeburg, on the southwest boundary, and

Meissen, on the south to southeast boundary, also sought territory on

the Teltow Plateau. Excavations at Düppel suggest a rudimentary border

control point, and artifacts date this site to about 1170. This

settlement was astride the route from the south to Spandau, and points

north. The conclusion is that the Ascanians shared a border at the south

side of the Teltow Plateau in 1170. Historians agree

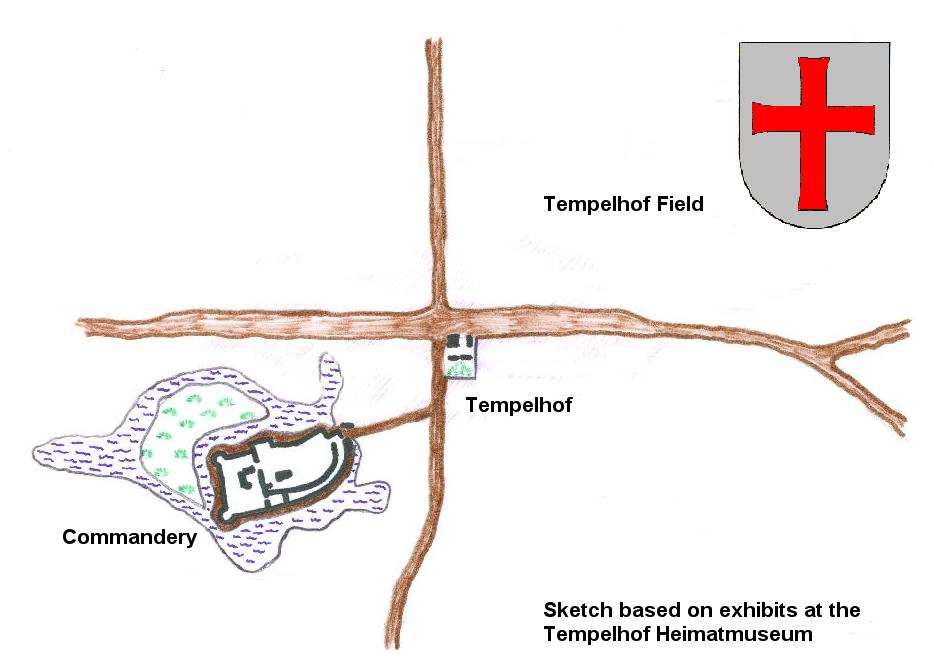

that the Knights Templar founded Tempelhof, but disagree about the date.

Albrecht is known to have given holdings at Werben on the Elbe to the

Knights Hospitalar in 1160. Founding of the settlement at Tempelhof

would have been some time after this date. Pommeranians and Wends

launched an attack around 1180, moving through Köpenick towards Juterbog.

Both Meissen and Lausitz countered this thrust, and forced the invaders

to withdraw the way they came. Lausitz then claimed Köpenick while

Meissen recovered or claimed territory up into Zehlendorf and

Lichterfelde. Therefore, it seems logical to assume that the Templars

had already taken up residence at Tempelhof by 1180, otherwise, Lausitz

or Meissen would have claimed part or the entire field. The only hard

evidence was found during excavations at the church in Tempelhof. They

determined that the church itself dates back to 1220-1230, and found a

partial foundation for an even older structure underneath it. Therefore,

it seems safe to assume that the Templars established a Commandery at

Tempelhof after 1160, possibly before 1180 and definitely before 1220.

It is likely that the Templars needed little encouragement from

Albrecht, and perhaps they even initiated discussions, that resulted in

their grant of Tempelhof. The Poor Knights of Christ

and the Temple of Soloman were also known as the Knights Templar, or

simply Templars. This order of "warrior monks" was founded by Hugues de

Payens and eight companions in 1118 AD, but the order was not formally

recognized until the Council of Troyes in 1128. Bernard of Clairvaux,

who reformed the Benedictans to found the Cistercians, drafted the

Templar Code of Conduct, which follows the same general lines as the

code he wrote for the Cistercians. The Templars, who were charged with

protecting Christians on pilgrimage to the Holy Land, were freed from

allegiance to anyone other than the Pope by a Papal Bull issued in 1139.

The Templars established holdings throughout Europe to

provide replacements and material to support their operations in the

Holy Land. Travelers – usually but not exclusively pilgrims - could seek

shelter at a Commandery (also called Preceptory) or with the "Locutor"

(village headman) of one of the orders of knighthood, or at an abbey of

one of the religious orders. These facilities were spaced apart a

distance equivalent to roughly 1-2 days of travel along important

routes, and most especially on those pathways to and from the Holy Land.

The interspaced commanderies and manors, each with a small contingent of

Templars, would have provided security along the route.

A Commandery would consist of a defensible enclosure, church

and outbuildings. Settlements would develop, since the Commandery or

manor would need both outlying villages and farms for food, and a

complement of basic trades (mill, smith, cooper, woodworker, etc.).

Replacements would have received orientation to the order and basic

military training at these locations, which would have been overseen by

an experienced – perhaps disabled or over-aged – knight. The abbey or

Commandery would recruit farmers and tradesmen, and – in the case of

Tempelhof – the Templars would escort the column or wagon train back and

provide area security for the settlers. History

credits Tempelhof as the first settlement, but does not state where this

settlement was. Work has been done to identify the location of the

original Commandery site and most conclusions are based on residuals of

the church, parts of walls, an underground access channel, and a pond. A

model and sketch were on display at the Tempelhof local history museum

and sketches have appeared in a number of reference works. The outworks

were probably the initial outpost and would have consisted of a wood

watchtower and defensive palisade. These were located on the southeast

corner of the intersection of present-day Tempelhofer Damm and

Alt-Tempelhof street, and the location came to be known as the "Hahnehof".

The church, church wall, manor, stables, and outer wall with at least

one tower and a gatehouse, were located on a small rise southwest of the

Outworks The Templars probably connected the ponds around this rise to

form a rudimentary moat enclosing the manor and a small island. The

island would have served as a garden plot and the moat as a fish pond.

As was stated earlier, all were probably constructed of wood and may

have been replaced in part by stone construction later. It is possible

that the frontier moved on quickly enough, so that the Templars did not

think it necessary to build a complete outer defensive wall of stone,

for no traces of such massive construction have been found.

The Commandery would have been known as "Tempelhof". The

original name of the settlement that grew next to it may have been "Tempelfelde",

if it followed the naming pattern noted elsewhere. The lands on an

estate were called the "Feldmark" and given the name of the village that

they were assigned to, therefore "Feldmark Tempelhof" would be Tempelhof

Field. The total Templar estate included at least 175 measured farm

plots called "Hüfe", roughly distributed as 50 plots in Tempelhof, 52 in

Marienfelde, 48 in Mariendorf and 25 in Richardsdorf (Neukölln). When

the farm community of Neukölln was reorganized into a village, it

consisted of 25 plots, and each plot was calculated to be about 10 "Morgen",

or 6 to 9 Acres. The size varied, because the land was divided in such a

manner that each plot contained some of the bad as well as some of the

good land. A plot was intended to grow enough to support one family and

one horse. A farm was called a "Hof" and it consisted of 1-4 plots (Hüfe).

Meadows, pastures and ponds were not considered in this count; stands of

wood were set aside, and marsh or bog land was partially excluded. These

were for common use according to agreements: for example, settlers

obtained reeds to thatch their cottage roofs from an allocated marsh.

Farmers paid annual rent (Pacht) and a personal "tax" (Zins).

In addition, they were required to deliver a specified quantity of

grain, meat and produce to the Templar kitchen, work a specific number

of days each year in the Templar manor fields, and give goods or

services to the village priest. There was of course, a levy to be filled

for military service in the margrave’s forces and the Templar could call

the farmers to arms in time of crisis. The Ascanians

aggressively recruited settlers. This was just good business, for their

income rose with each increase in property under cultivation, and their

territorial claims became more secure. Ascanian status in the German

Empire was dependent upon able-bodied men willing to fight for their

homesteads "in the Ascanian Cause". From a settler’s point of view, "Old

Europe" was getting overcrowded and the land was being worked out.

Floods at that time in Holland only made the congestion worse. The

Ascanians offered inducements to attract homesteaders, for example,

suspension of obligations for a period of time as compensation for

resettlement, particularly for skilled tradesmen. Social pressures

undoubtedly forced some to move east, while others would have answered

the call to convert the heathen. Like any comparable cross-section

throughout history, some people were ready to move for the sheer

challenge, the relative freedom, and the pure adventure of a life on the

frontier in the "Wild East". Templar recruiters would

visit a number of villages and cities to recruit and collect candidates.

Elements would have been assembled at Magdeburg in a wagon train, which

have followed a route from Madgeburg, through Saarmund, then pass south

of Potsdam, and continue on to Tempelhof, and perhaps to further

destinations eastward. Upon arrival, lots were probably drawn for

allocation of plots and it is likely that all would have worked together

to build dwellings, so that the process of clearing and cultivation

could begin. Excavations at Düppel show that some of

the first settlers were Wends. No sources describe the daily routine in

area settlements, nor do they show the degree of resistance – if any -

that took place during the settlement process. The findings at Düppel

suggest that there was some degree of peaceful interaction between the

two races. The settlement that grew around the ford

across the River Spree enjoyed the advantage of being on the main water

route, as well as at the crossroads of the major land routes. Although

established later, the community of Berlin-Kölln prospered quicker

because of these advantages, and became the regional center for

commercial enterprise. Berlin grain and timber were hallmarks of quality

at that time. The success of the Ascanians was

recognized in 1230, when the Margrave of Brandenburg was given

electorial powers in the Imperial Diet. The Elector of Brandenburg thus

became one of the very few allowed direct participation in the election

of the German Emperor. This clearly established their position in the

upper echelon of the Empire’s power structure. Spandau, the settlement

next to their seat in the Mark Brandenburg, was given city rights on 7

March 1232. The Templars are credited with

establishing banking services, using the network of their commanderies

and manors throughout Europe. For example, a merchant would receive a

letter of credit based on money or goods that he deposited at a local

Commandery. The letter could then be presented for payment, minus a

handling charge, at any other Templar holding. The Templars amassed

great wealth and vast estates over time, and this proved to be the

primary cause for their downfall. Phillip VI "the

Fair", King of France, ordered the arrest of the Templars in France on

Friday, 13 October 1307. Using charges similar to those used earlier

against the Cathars and later by the Inquisition, the Templars in France

were arrested and questioned under torture. The Grand Master, de Molay,

initially confessed denying Christ and trampling on the Holy Cross,

while resolutely denying charges of homosexuality during initiation

rituals. However, he publicly recanted his confession made under

torture, and was burnt at the stake on 18 March 1314. Accounts of De

Molay's dying words have him calling the King of France and Pope Clement

to meet him in a tribunal before God within the year, and both did, in

fact, die within that time. The Templars were a

prominent item on the agenda of the 15th Council at Vienna, which Pope

Clement V opened on 16 October 1511. Under pressure from Phillip of

France, the council resolved, and the Pope decreed, the disbanding of

the order. Templar holdings in Germany were turned

over to the Order of Knights of the

Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem, or simply the "Knights

Hospitaller" (also called the "Knights of Rhodes" from 1309 to 1522, and

"Knights of Malta" since 1530). The Margrave had sent

his representative to claim the keys to the Tempelhof Commandery, and –

of course - the estate’s revenues, until the issue had been resolved.

Margrave Waldemar recognized the disbandment decree in a treaty dated 29

January 1318. The Change of Command Ceremony at Tempelhof appears to

have been just a change of clothing, in which the knights removed the

white surcoat with the red Templar cross, and put on the black surcoat

with the white Maltese cross of the Hospitallers. Names on documents

dated before and after this event appear to be the same.

The next change of command caused much more severe problems. Margrave

Waldemar was reported dead and buried at Chorin Abbey on 14 August 1519.

The death of Waldemar, last of the Ascanians, generated a flood of

claims and counter-claims against Mark Brandenburg and various sections

within it. The issue was brought before the "Reichstag" (Imperial Diet)

at Nuremburg in 1524 for resolution, where it was decided in favor of

the Wittelsbach claim. However, the Wittelsbach Margrave Ludwig was only

8 years old. and this lack of majority caused another scramble for

control of the guardianship. Fresh

fuel was added to the controversy in the summer of 1348, when both the "Black

Death" and a wandering "pilgrim" came to the Mark Brandenburg.

The "Black Death" or Bubonic Plague spread up through Europe

from Venice between 1348 and 1350. It is estimated that this epidemic

killed 25,000,000 people - about one quarter of the total European

population. The pilgrim stopped at Magdeburg and told

the Archbishop that he was Waldemar, the last Ascanian Margrave.

According to his tale, he had buried another person in his place at

Chorin Abbey, and had gone on a pilgrimage to repent for his sins.

Heathens had captured and imprisoned him, and he had only recently

managed to get loose and return. Now he was ready to return to his

duties. Nobles and cities declared for or against Waldemar, who began

his "reign" in 1348. In September 1348 he rewarded the twin cities of

Berlin-Kölln for their support of his claim, by granting them a portion

of the revenues from Tempelhof, Mariendorf and Marienfelde.

The years immediately following were marked by severe losses due to

Plague, to violent persecution of the Jews (who were supposedly

responsible for the plague), to the civil war between the followers of

Margrave Ludwig and the Pretender Waldemar, to the disruption caused by

nobles (who were still pressing territorial claims), and to economic

depression caused by the breakdown in commerce, which would have been

felt throughout the region. The King of Sweden was

asked to mediate and he decided in favor of the Wittelsbach claim. The

twin city Berlin-Kölln apparently ignored this ruling. Margrave Ludwig

the Elder was preparing to besiege both Spandau and Berlin-Kölln when

the cities requested a truce, which he granted for the period 2-31 July

1351. Margrave Ludwig the Elder probably set up his main camp on

Tempelhof Field, for it was here that delegates signed the peace treaty.

This document, which sealed the peace between Margrave Ludwig and the

twin cities of Berlin-Kölln, is also the first document that formally

mentions Tempelhof Field. It was signed on Friday, St Mary Magdaline’s

Day (i.e. 22 July), 1551 "to velde in dem Dorpe to Tempelhove" (in the

field of the village of Tempelhof). Waldemar the Pretender was exposed

as a fraud and an uneasy truce was in effect. Emperor

Charles IV promulgated the famous "Golden Bull" (Aurea Bulla). This was

a fundamental law of the Holy Roman Empire, signed during the Nuremburg

Diet in 1356, and modified at the Diet of Metz in the Fall of the same

year. The most important clauses established that the emperor would be

chosen by election and resolved the question that the electorial vote

was to be vested in seven principalities versus ruling families. Now

recognized, the Wittelsbach Margrave withdrew and left his governors to

deal with the rebellious nobles. Although the issue was settled for

Tempelhof and Berlin-Kölln, the conflict itself lasted many more years.

The Knights of St. John reorganized the outlying farms on the

eastern fringe of Tempelhof Field and established the village of

Richardsdorf (today’s Neukölln) in 1360. This may have been a measure to

improve security and stability. This charter is the only one of its type

for any village in the Mark Brandenburg that has survived to this day.

The Wittelsbach family gave up its claim to the Mark

Brandenburg on 15 August 1573, and the territory reverted to the

Emperor, Charles IV, and to the Luxemberg family. Things improved

slightly under the Emperor’s direct guardianship. However, after his

death in 1578, the Mark Brandenburg was divided among his sons and the

conflict raged anew. Strong-willed nobles again intimidated, terrorized

and manipulated. They stole money, valuables and goods quite literally

by highway robbery, thereby earning the name "Robber Barons"

Merchants were the first to suffer their attacks, for small

groups on the open road were easy prey for the knights. Goods were

plundered and the merchants were killed or held for ransom. Attempts by

the merchants to convoy or hire bodyguard troops were met by even larger

bands of Robber Barons. When the robbers graduated to capturing and

either ruling or ransoming settlements and towns, cities in the Mark

Brandenburg, including Berlin-Kölln, formed a protective league called

the "Landwehr". This did not save Berlin-Kölln, which was taken and

forcibly ruled by the von Quitzows in 1402. The von Quitzows and their

allies at this time controlled most of the territory around Tempelhof

Field, and Robber Barons in general, had free run in the Mark

Brandenburg. Compared with the Wittelsbachs, the Luxemburgs seem even

less interested in conducting Brandenburg’s affairs. Sigismund used

Brandenburg as collateral for a loan when he needed money to back his

claim to the Throne of Hungary, and he reportedly pawned and redeemed

Brandenburg several times. Berlin-Kölln sent a

delegation to seek his aid in ousting the Robber Barons. The timing was

fortunate, for it was close to the time for an imperial election.

Sigismund agreed to send his field captain, Frederick VI, "Burgrave" of

Nuremburg. Frederick VI was a Hohenzollern and this

family originally came from Swabia. In a round-about way, the

descendents of the original ruling tribes had returned to the Mark

Brandenburg. They would continue to rule for just over 500 years:

promoted successively from Margrave and Elector to King and finally to

Emperor of Germany. Frederick VI, accompanied by a

small bodyguard, arrived in Berlin-Kölln on 7 July 14l2. However,

instead of confronting the Robber Barons, he went on a tour of

inspection. Only afterwards did he invite the nobles to dinner,

attempting to use persuasion. However, they remained intractable. One of

them reportedly said that he would not give in "even if it rained

Nurembergers". Frederick VI led a force of local citizens and his

bodyguard against the Robber Barons but was defeated at Kremmer Damm in

the north of Berlin. He withdrew and regrouped,

requesting the loan of "Faule Gretel" (Lazy Gretel) and sent for a force

of Franconian Knights. "Lazy Gretel" was the super weapon of the age. It

fired large caliber bronze cannon balls that effectively took castles

apart. The gun got its name because of the amount of time it took to

move, site and load. Frederick VI’s next campaign was successful. The

Quitzow fortresses, including the "impregnable" fortress at Friesack,

were stormed and the von Quitzows and their allies were killed, captured

or run out of the Mark Brandenburg. Frederick VI had

originally ensured his promotion to governor of the Mark Brandenburg by

a loan of 100,000 gold guldens. A further loan of 200,000 gold guldens

moved the Emperor Sigismund to announce at the Council of Constance on 5

April 1415, that he had raised his governor in Brandenburg to Margrave

and Elector of Brandenburg. Frederick VI renamed himself Frederick I, in

keeping with the customs of the time, and assumed office even though the

formal investiture did not occur until 18 April 1417.

The leading citizens of Berlin-Kölln formally reviewed property boundary

markers in an annual procession that took place on St. Bartholomew’s

Day, the 24th of August. The boys would be given their first

lesson in citizenship, for at each marker the mayor would show each boy

the specific marker, admonish him never to move it or deface it, switch

him to ensure that he noted the lesson, and then give him a sweet cake

to help him to remember it. One of these annual boundary processions led

to a short and bloody confrontation between the Hospitallers and the

citizens of Berlin-Kölln. Commander Nickel von Colditz

and several of his knights were present when the councilmen determined

that a boundary marker had been moved. The move was in favor of

Tempelhof and this was sufficient proof of the misdeed in the eyes of

the Berlin-Kölln councilmen. Although no documents survived, eyewitness

accounts have preserved the tale. Heated words were exchanged and the

Hospitaller Commander sent for reinforcements from the Order’s eastern

holdings and issued the call to arms to inhabitants of Tempelhof,

Mariendorf, Marienfelde and Richardsdorf. The Hospitaller assembled

their attack force of about 500 cavalry and farmers from the four

villages on the northern portion of Tempelhof Field. The knights and

villagers launched a dawn attack on the city defenses at Köpenicker Tor.

However, either the defenders were forewarned, or perhaps had observed

the preparations. Once the Hospitaller force was fully engaged, the city

cavalry sortied from Gertraudtentor and attacked the knights and

villages on the flank and rear, while the city infantry stormed through

the gate in a coordinated frontal assault. The knights retreated towards

Köpenick and both sides appear to have suffered heavy losses. Less than

a month later, in September 1455, the Hospitaller sold the village of

Tempelhof, the manor, and all that belongs to them; the village of

Richardsdorf with its meadow, bog and moor; the village of Marienfelde

with the windmill, and the village of Mariendorf with the Hegesee at

Teltow, for "vier und twintig hundert schock, negen und druttig schock

und viertig groschen an bemischen gelde" (2,459 Schock, 40 Groschen, in

mixed coinage). A "Schock" (= 60 Groschen) was the measurement term used

to show the value of property and buildings for tax purposes.

Tempelhof Field’s steady but staid

progress through history was interrupted on 15 July 1525 - the day the world was

supposed to end. The Elector’s court astrologers had forecast the coming of a

great flood, which would sweep across and destroy the entire Mark Brandenburg.

Elector Joachim I took the warning very seriously and resolved to save what he

could. When the storm broke at noon of the appointed day, he packed his

possessions, family and court into carts, and moved the parade expeditiously to

the highest point in the region atop Tempelhofer Berg (now the Kreuzberg).

Troops cordoned off the approaches to prevent the stricken rabble from storming

the hill when the flood came. Luckily for the Berliners, this never happened.

Joachim must of had time to closely examine the hilly rim of Tempelhof

while waiting for the flood, for in 1555 he ordered vineyards planted on

these slopes (Tempelhofer Berg and the "Rollberge" or Tempelhof Hills).

Some of the plants may have come from the Marian Cloister near Spandau,

for Joachim I ordered 200 grape vine plants from Abbess Schapelow there,

for shipment to Berlin. Spree Riesling became popular in the 14th

Century, and was shipped by wagon or boat to Hamburg, Flanders, Poland

and Russia. The population

converted to the reformed or Lutheran faith In 1559 following the example of the

Elector. Two local legends may well date back to this time, which, if they

provide an insight into the values of the period, show these as a combination of

Christian values, myth and superstition. Little People:

Once upon a time, long ago, when a great forest covered the field and it was far

from the city, a poor woman lived there alone in a simple hut. One evening, two

of the little people came out of the forest and asked her for the loan of a

bowl. She lent them the bowl willingly, and they left, carrying the bowl between

them. The next morning, the woman was surprised to find the bowl before the door

of her hut, and even more surprised to find that it contained a piece of

delicate roast meat. On following evenings, whenever the little people requested

the loan of something, the object was always returned the next morning with a

small gift. The woman became very curious, and one evening secretly followed the

little people. She saw them enter a cave and managed to follow them unnoticed.

Deep in the earth she came upon a large, brightly lit kitchen filled with cooks

busily preparing a meal. The woman was able to withdraw without being seen and

went back to her hut. When the little people came the next time, she said

nothing, but added a small bundle of dried herbs to the article that they asked

to borrow. The next morning, and many mornings thereafter, there was a silver

coin before her door. It was enough to allow her to live well without worry, and

went on for quite some time. Gradually, as more and more people moved in and

settlements grew, and the peace of the woodlands was frequently disturbed by the

noise and sounds of everyday life, the visits by the little people became less

and less frequent. When the ringing of church bells was heard, the little

people, who could not abide that sound, packed their things and moved away – no

one knows where. The Poor Widow of Tempelhof:

There once was a woman, whose husband had died, who had to work very hard to

earn enough to support herself and her young son. One day, they were following

the path across Tempelhof Field on their way to Berlin. The woman was lost in

thought and worries, when she was started by a shout from her son. He stood

before a hole in the ground, surrounded by multi-colored rays of light coming

out of the hole. She rushed over and saw that the bottom of the hole was covered

by gold, silver and jewels. Shouting for joy at her good fortune, she quickly

knelt and scraped several handfuls into her apron, which she quickly bundled up

securely, and then hurried on her way. Suddenly, she remembered her son, and,

when she turned around, saw him twisting and squirming as he disappeared into

the hole. By the time that she ran back, the earth had closed over him and

became as hard as stone. Scraping, scratching and digging did not help – the

earth would not release the boy. When night came she was forced to go home, but

she returned the next morning and every morning thereafter. However, she never

found any sign of her child. One Sunday morning, as the church bells called to

services, she knelt and began to pray. She was startled by the touch of a small,

soft hand on her shoulder, turned, and found her son sitting next to her. The

child did not speak, but only beckoned her to follow him into the hole. She did,

and found herself in a room with walls that were lined all around with

containers holding the souls of unbaptized or abandoned children. The child took

the top from one of the vessels and showed her the small, torn soul within.

"That is my soul," whispered the boy, "it broke when you forgot me for the

treasure". "Sew it together again and I will be free." The woman pulled thread

from her smock and immediately started to work. The child screamed and rolled in

pain, but she did not allow herself to be distracted and hurried to quickly

finish. The boy cried out for joy. He was free. She grabbed him and quickly

left. As she came out of the hole, she again saw the aura of colored lights and

blinking treasure. This time, she ignored it and rushed on, happily hugging her

child. Wealthy city dwellers started seeking investment

opportunities in lands adjacent to city holdings at the close of the 16th

century, and parts of Tempelhof Field were sold off on speculation.

Berlin’s treasury was in poor shape at the time, and the council decided

to sell its interest in Tempelhof, Mariendorf and Marienfelde to its

sister-city, Kölln. Johann Köppen, the Elector’s Councilman, purchased

the Templar Manor. Katharina, the wife of the Elector, acquired and

reunited the Templar Manor with the village of Tempelhof Village in

1601. The properties changed hand several times following her death in

1602. Bubonic Plague appeared again in Marienfelde in

1611. The disease was first experienced at the farmstead that served as

the village inn, and within a few days, all of the inhabitants were

dead. Bubonic Plague would terrorize villages and towns throughout

Brandenburg for the next two years. Plague was

quickly followed by inflation and scarce money in a Europe moving

steadily toward war over religion. Uncertainty caused hoarding and

restricted trade. The declining number of coins that remained in

circulation had generally been "clipped". This prompted the Berliners to

dub this period the time of the "Kipper und Wipper", referring to

"Kipper", the persons who clipped pieces from coins, and "Wipper",

referring to the scales that merchants had to use to weigh the coins to

ensure full measure of payment. Serious as these issues were, they were

merely the opening scene of a much, much larger disaster.

The Bohemian Revolt started on 23 May

1618, when a group of Protestant radicals tossed the Hapsburg Emperor’s

delegates, Martinitz and Slawata, out the window of the council chamber in the

palace at Prague. This war in Bohemia from 1618 to 1623 was

the first in a series of wars that have come to be called the "30 Years

War" in Europe. The others were the Danish War (1624—1629), the Swedish

War (1630—1635), and the French-Swedish War (1635—1648). Each conflict

has the dubious distinction of being bloodier and more devastating than

the previous, and although religion was the proclaimed issue, politics

and power were the more prominent cause. Elector Georg Wilhelm tried to

maintain Brandenburg’s neutrality. He led negotiations which resulted in

the marriage of his sister to King Gustav Adolf II, of Sweden, who was a

major power in the Protestant camp. He appointed Graf Schwarzenberg to

chair his Privy Council. Graf Schwarzenberg had strong ties with the

Catholic Hapsburgs and he was effectively "chancellor" in Brandenburg by

virtue of his position on the Elector’s council. However, the Elector’s

neutrality program was nullified by Brandenburg’s position in roughly

the center of the more aggressive combatants, and it became an assembly

area used by both sides. Essentially, it was occupied by one side or the

other throughout the conflicts. The Swedes moved into the Mark

Brandenburg in 1651, but did not leave entirely until they were forced

out in 1678. Tempelhof was pillaged and looted for

the first time in 1620, and was revisited again in 1626/27, when a force

of about 100 "Landesknechte"(mercenaries) were forcibly quartered on the

field and in the village. In both cases, the troops brought disease with

them, for there were widespread reports of plague, dysentery and

cholera. Imperial troops were active throughout the region and occupied

Berlin in 1628 and again in 1630 under Wallenstein. Plague reappeared in

1631/32 and killed a third of the population in Mariendorf. This time it

was probably brought in by the Swedes, who re-entered the region in

mid-l631. Unbelievably, things actually got worse following the Peace of

Prague. Severe epidemic waves of plague, cholera and dysentery were

interspersed with widespread atrocities committed against the dwindling

civilian population by wandering bands of unemployed mercenaries, for -

by this time – there was very little left to forage and nothing left to

plunder. In March 1652, roughly

three years after the war ended, Elector Frederick Wilhelm ordered that a census

be taken. His enumerator in the Teltow District, which included Tempelhof, was

Michel Klinitz, who recorded: "...Only the farmers Rohde and Teyle remain on

their farms." Volumes have been written on the subject, but a true measure of

the magnitude of the disaster called the "30 Years War" is clearly and

dramatically demonstrated by a simple statistic. at the start of the war,

Tempelhof was a flourishing village of 50 large families, and after the war,

only the remnants of two families remained in a wasted community.

The Elector, in a manner similar to that of the leaders of other small

states in Europe, contracted-out portions of his army and small navy.

For example, Prussian troops were hired by the King of Denmark, who in

turn sub-contracted their services to William of Orange in Ireland in

the late 1690’s. Prussia, like other small states in Europe, actually

became a major military power without fighting a war in its own cause.

Frederick III added another title on 18 January 1701, when

the Elector and Margrave of Brandenburg crowned himself King in Prussia

during lavish coronation ceremonies. He took the name Frederick I and

personally led the festive coronation procession over 400 miles back to

Berlin. In excess of 1,800 carriages and a huge escort paraded through

throngs of well-wishers and gaily-bedecked towns and villages along the

route. When the new king arrived in Schönhausen, on 17 March 1701, he

determined that preparations for the official reception in Berlin were

unsuitable. He stopped the procession for nearly two months, and finally

entered Berlin on 6 May 1701. The coronation reception has been called

one of the greatest spectacles of all time. It was only in keeping with

the character of the new monarch, who managed to bring Prussia to the

brink of financial ruin. His son,

Frederick Wilhelm I, was a complete change. Frugal, active and very observant,

he roamed the streets of his domain on personal inspection tours, called "Caning

Tours", because the monarch dealt swift punishment with his walking cane.

Idleness was unlawful in Prussia. Even street peddlers were required to engage

in some productive endeavor instead of idle gossip when between customers. The

king abolished the gala court maintained by his father, sold the gaudy palace

trappings, and severely scaled down the residence staff. He revised the judicial

system and reformed administrative offices, to establish the basis for Prussian

Civil Service. Frederick Wilhelm I is also noted for starting social reforms

that produced a rudimentary social welfare system and an expanded public school

system. He was reportedly deeply religious and, at the same time, known for

drunken revels and pranks during his staff meetings, which were called the "Tobakskollegium"

(Tobacco Council). He gave Berlin a military police force and taxis (horse-drawn

carriages called Droschken), expanded the city’s territory, laid out streets,

and ordered an extensive building campaign. His cousin,

George II of England, called him "my brother-in-law, the Sergeant".

European courts amused themselves with stories of the latest antics of

the "Prussian Drill Sergeant," and history calls him the "Soldier King".

His passion was the Prussian Army, and most especially his personal Life

Guards Infantry Regiment, the "Lange Kerle" (Tall Guys).

He initiated a national draft and increased Prussia’s

standing army from 50,000 to 80,000, not including reserves, militia and

home-guards. This force was drilled to the point where only one will was

recognized - the King. It is not known when Frederick Wilhelm I first

decided to use Tempelhof Field but chronicles record his presence at

various times on and around Tempelhof Field after about 1719.

The first recorded maneuver held at Tempelhof was in the

Spring of 1722 and these exercises became annual events. The king

required that the army demonstrate its ability and readiness to conduct

operations before the start of the campaigning season. Evolutions during

this first review lasted two weeks and involved six Berlin infantry

regiments, six squadrons of hussars and the mounted "Gens d’armes"

Regiment. These annual maneuvers also provided an opportunity to

showcase capabilities before potential clients, since the Soldier-King

continued his father’s practice of contracting-out troops.

The farmers were told to clear the field prior to the

exercise and then were allowed to cultivate it after maneuvers were

completed. As time went on, military use of the field started to

seriously infringe upon the growing season. Larger contingents of troops

used successively larger segments of the field. Finally, in response to

complaints about economic losses, the Prussian Treasury agreed to pay

maneuver damages to Tempelhof farmers. The initial budget was 1200

Talers, but this had been raised to 2000 Talers by the start of the 19th

Century. A parade was held at the close of maneuvers

during the early years. A contemporary chronicle has survived, which

records the events that took place during one of these parades. "The

king was up and astride his horse by 2 A.M. on major review days. The

regiments would file out through Kottbuser Tor to Tempelhofer Berg (now

Kreuzberg), where they would march past the king. Then the infantry

would assemble in line formations and the king would ride the front

accompanied by martial music and saluting flags. After this, the king

would return to the center front, where the signal cannon was emplaced.

Field chairs had been set up there for the princes, who each received a

piece of buttered bread, which they thoroughly enjoyed, from a page who

carried two packages in his pocket for that purpose. After breakfast,

the regiments would perform their wheels and drills, and as the final

evolutions were completed, grenadiers would toss wooden grenades to

startle the cavalry. The Berlin public, and especially the on-looking

boys, thought that this was a great show. During the return march to the

city, the queen and princesses would stop at the city gate, to see which

unit the king favored. The march route led to the palace, where all of

the infantry would again pass in review to salute the queen, who waited

here. The performance ended after the password was given out, about 5

P.M. Following this, all officers would assemble in the hallways before

the king’s apartments, where benches had been set out for their use and

relaxation." Several of the early reviews at

Tempelhof were so large and imposing, that they are in a class all by

themselves as a rank of "super parades". One of these was given in honor

of the state visit by August the Strong, King of Poland and Elector of

Saxony. The Alert Order given by the Soldier-King for this event has

survived: "Review for the King of Poland and

Elector of Saxony, August the Strong: Parade and Drill Order for cavalry

and infantry, and the day of the event, will be announced later. Troops

to assemble at 0100 hours before their Captain’s quarters, and then

march to their Commander’s quarters at 0200 hours, where they will be

formed into battalions." More than 16,000 men

took part in this review, divided up into 20 infantry battalions and 20

cavalry squadrons. The garrison troops were called

out again for an even larger spectacle on 12 June 1733, when a Festive

Review was ordered as part of the ceremonies celebrating the wedding of

the Crown Prince. Frederick II, who was known to history as "the Great"

and to his people as "Old Fritz", married Elisabeth Christine of

Brunswick-Bevern in keeping with the arrangements made by his father.

"Members of the leading families in 59 coach-and-six were escorted from

Charlottenburg at 5 A.M. by a throng of mounted gentlemen to the tented

pavillion that had been set-up on Tempelhof Field. Twenty battalions and

twenty squadrons drilled and wheeled there to cannon-fire commands until

the wedding party returned to Berlin at 1 P.M. The return march by the

regiments and subsequent review before the palace lasted until 4 P.M."

The Soldier-King ordered that a medallion be struck to commemorate

the event. The reverse of this medallion shows the parade scene at

Tempelhof Field, with the edge of the Kreuzberg and the Rollberge in the

background, and a cavalry charge in progress on the grounds of the

present airport terminal building.

Both the Soldier-King and Frederick the Great had severe problems with

desertions from the Prussian Army. This is not surprising, considering the

brutal discipline and the fact that most of the troops were recruited or

impressed against their will. The Soldier-King implemented one countermeasure

that directly affected the Tempelhof Farmers, when he emplaced a gun atop a hill

on the north side of Tempelhof Field. This hill, which lies just north of

present-day "Platz der Luftbrücke", came to be known as "Alarm Cannon Hill".

When a deserter was reported, the gun was fired to call the farmers out to "beat

the brush" and search the field. Ulrich Bräker, a Swiss "recruit", left us an

eyewitness account of what happened to those deserters who were caught in 1756:

"...we were forced to watch while they were made to run the gauntlet

eight times in both directions, through a narrow lane formed by two

hundred men with switches, until they fell, out of breath. The next day

it began again. Tattered rags were stripped from torn backs, and they

were beat anew until blood streamed and scraps of flesh hung down over

their breeches..." Military desertions continued

and were compounded by the serious economic effect of citizens also

fleeing the city and country to avoid being drafted. The Soldier King

ordered that a wall be built around the town. The stated intention was

to ensure the collection of revenue and prevent smuggling, earning the

name ‘Zollmauer" (Customs Wall), but – like a later "Berlin Wall" in the

20th century - the real intent was to prevent depopulation.

Even the institution of the death penalty did not stop the exodus. The

Soldier King was forced to release Berlin from the military draft

system. Again, as with the "Berlin Wall" of the 20th Century,

there was an immediate increase in population, as citizens moved into

the city to avoid military service. On 16 October

1737, an observer on Tempelhof Field would have had the opportunity to

witness a very unusual event, when a small Austrian force captured and

ransomed Berlin. While Frederick the Great and the bulk of the Prussian

Army were engaged in the south, Prince Karl of Lothringen had the

inspiration, and in the person of General Hadik, the right person, to

launch a daring scheme. General Hadik quickly assembled a small, lightly

armed Austrian force, which has been reported from 5400-7000 men, and

led them in forced marches to the gates of Berlin. On 16 October, 500

hussars swerved west across Tempelhof Field to attack Potsdamer Tor,

while the main body mounted an attack on the Schlesischer Tor - both

gates were in the outer ring of city fortifications. The attack at

Schlesischer Tor carried through to the open ground in front of the

inner defensive ring, and the Austrians threatened Kottbuser Tor.

General Hadik sent a trumpeter with the demands: surrender the city and

pay a ransom of 500,000 Taler within 24 hours. True, the Austrians

shuffled their troops to give an impression of greater numbers than were

actually engaged. Even so, it was a pretty audacious demand, for the

Berlin Garrison was about 7000 strong, behind strong fortifications, and

supported by the population of the town (estimated between 90,000 and

150,000)! Lieutenant General von Rochow was obviously very confused and

apparently he expected a much larger effort. He held back reserves and

only committed defenders piecemeal to the city defenses. These small

units were quickly overcome by the Austrians, who then started

plundering. General Rochow withdrew the garrison to Spandau and left

word that he was quitting the town and leaving it to the discretion of

the Austrians. However, by now General Hadik had his own problems. He

did not have sufficient forces to take Berlin and word had reached him

that a relief column under Prince Moritz of Anhalt was marching hard to

the city’s defense. He dispatched a small group of officers to collect

the ransom (200,000 Taler in money and notes of exchange), assembled his

troops, and retreated hastily along the eastern fringe of Tempelhof

Field. On the way out, the Austrians sacked villages in their path for

Buckow was plundered according to the village chronicle. Prince Moritz

and the relief column arrived on 18 October, and hussars were sent in

pursuit of the Austrians, who lost some 60 men and one wagon loaded with

money during the "get-away". Three years later, the

Russians advanced on Berlin. The Cassocks of their advance guard swept

across Tempelhof Field on 1 October l760. The main body, under General

Tottleben, arrived four days later and 5000 Russians attacked the city

defenses at Schlesischer Tor. The initial attack was broken by the

city’s 1500 defenders, and General Tottleben ordered his artillery to

soften the town defenses in preparation for a second attack. Six cannon

and a number of howitzers bombarded the town and the second attack wave

was launched, but also failed. Seeking another opening, the Russians

swung left on the defenses. The artillery was moved to emplacements on

Tempelhof Field and on the hills to the north of the field, and a third

attack was launched. This too failed and the Russians camped on

Tempelhof Field for the night. A relief force of 8000 men under the

Prince of Wurtemburg was able to reinforce Berlin that night, and

General Tottleben withdrew most of his force from Tempelhof Field

towards Köpenick during the morning and afternoon of 5 October. That

evening, a Russian Corps under General Czernitscheff moved into

positions on the east side of Berlin and General Tottleben was able to

bring his main force back to Tempelhof Field. Both Russian elements

launched a simultaneous, two-pronged attack on 6 October, which also

failed. A second Prussian column under General Hülsen marched rapidly

toward the city and reached Zehlendorf that same evening. On the morning

of the 7th, the Russians plundered and burned Schöneberg, then retreated

across Tempelhof towards Köpenick, while General Hülsen moved his troops

into the city. Battles were fought again that day and again the Russians

were thrown back. However, Marshall Lascy arrived that afternoon with

the main Austrian Army and demanded the surrender of Berlin. The War

Council considered the alternatives and decided to surrender the city,

for although the defenders now numbered 16,000, the combined, the

Austrian and Russian opposing force was more than 45,000. On the next

morning, 8 October 1760, the city was turned over to General Tottleben

and the ransom demand was made: Berlin was to pay 15 tons of gold and

200,000 Taler in coins. The money was collected. along with the gold. by

a form of head tax (each person contributed a share) and given to the

Russians who withdrew from Berlin on 12 October 1760. Farms in Buckow

were plundered and there are reports of a number of atrocities committed

during the withdrawal of the Austrian and Russian forces.

The humble beginnings of the air age date from 5 June 1785, when Joseph

and Jacques Montgolfier launched a hot-air balloon with a lamb, a duck

and a chicken as passengers. The flight was successful and the

passengers survived. J.F Pilatre de Hazier then made the first manned

flight in a Montgolfier balloon on 15 October. But the crowning

achievement in aviation’s first year occured on 21 November, when Mr.

Hazier and Marquis Francois Laurent d’Arlandes flew a Montgolfier

balloon from the summer palace at La Muette to the nearer environs of

Paris. Man had realized a dream dating back to antiquity and it was not

long before that realization became a commercial enterprise.

Jean Pierre Blanchard started demonstrating the new invention

at various cities in Europe, and it was in this manner that the

Berliners were introduced to the wonders of flight on 27 September 1788.

Blanchard set up the apparatus on the parade ground outside of

Brandenburg Gate. City officials called for the public to maintain peace

and order, "and not to make themselves punishable by loud disturbing

outcries or other disorders, including injuries, climbing trees, or

trampling the fields…" City officials made it very clear that

violators "will be taken into custody, without regard to station or

status, and severely penalized." The warning was

to no avail. The squadron of dragoons, that had been detached to guard

the large, cordoned-off area, had to be reinforced with 2,000 men in

order to keep the enthusiastic Berliners beyond the barrier. Because of

the distance from the city, physicians, surgeons, and substantial

quantities of bandages had been brought in to provide immediate first

aid, should this be needed. Finally, the long anticipated moment

arrived. The balloon expanded and rounded out as it filled. Blanchard

climbed aboard and two large dogs were helped into the basket as the

Berliners applauded and cheered. A few sandbags were tossed out, and the

balloon lifted-off and rose higher and higher. Suddenly, the onlookers

gasped as a bundle suddenly tumbled from the balloon. It unraveled and a

small parachute opened, that supported a smaller basket containing the

two dogs, who survived the adventure without injury. The weight loss

caused the balloon to accelerate upward, where winds caught it and drove

it rapidly away. Blanchard was followed on the ground by a throng of

riders and horse-drawn vehicles. They caught up with him when he finally

landed near Buchholz, and Blanchard was brought back to Berlin at the

head of an enthusiastic procession. Berlin had its

introduction to flight and balloons became the rage. Of course it became

obligatory, that major festivals would now have an air show. Even high

fashion was represented, for there were several "Balloon Hats a la

Blanchard" for Milady. The balloon remained a toy for

nearly a hundred years before the military came to accept its

reconaissance value and military potential. In that interim, several

important historical events would take place on or near Tempelhof Field.

Where "The Soldier-King" and "Old Fritz" energetically brought Prussia

to political prominance within the European community, it seems that

their successors lived on their laurels for several decades. It was

during this period that Napoleon rose to power in France, crowned

himself Emperor, and started realigning European relationships. Austria,

Prussia and Russia were his immediate concerns. During the first

Coalition War, Prussia allied herself with Austria and a small force

entered France. They were stopped at Valmy on 20 September 1792. After

the peace treaty was signed, Prussia remained neutral through the

remainder of the Coalition Wars, being preoccupied with her eastern

border and new acquisitions during the partition of Poland. Although he

concentrated first on Austria, Napoleon had not forgotten Prussia. On 5

November 1805, Archduke Anton of Austria, Emperor Alexander of Russia

and King Frederick Wilhelm III of Prussia reached agreement during the

Council at Potsdam. Prussia would serve as a negotiator between the

French, Austrians and Russians, and if the French did not pull out of

Germany, Holland, and Switzerland by 15 December 1805, then Prussia

would enter the conflict. Napoleon called Prussia’s bluff, for it became

just that after he soundly defeated the Austrians and Russians at

Austerlitz (2 December 1805). Frederick Wilhelm III was forced to sign

the Treaty of Schönbrunn on 15 February 1806, which bound Prussia to

France. Napoleon wanted Prussia eliminated, not just

neutralized, and he tried various schemes to force Prussia out of its

neutrality. He finally succeeded when he ensured that the Prussians were

aware of the contents of apparently secret negotiations with Russia and

Britain for Prussian holdings in Poland and Hannover. The Prussian Army

of about 100,000 strong was called to readiness on 9 August 1806, and

this was followed by the last great review In Berlin before hostilities.

The Prussian troops who marched out of Berlin in September 1806, were

not the same caliber army that had won the Seven Year’s War. Although

numerically superior to the French, they were badly led and Napoleon

easily defeated them at the twin battles of Jena and Auerstädt on 14

October 1806. Napoleon quickly marched toward Berlin,

and the first French troops entered the city on 24 October. The advance

guard bivouacked that evening on Tempelhof Field. On 27 October,

Napoleon personally entered Berlin at Brandenburg Gate, and the French

occupied the city until the war debt had been paid. A Quartermaster’s

receipt from Schöneberg, which served as a headquarters for a French

Corps, verified that 8 noncommissioned officers and 500 men were

quartered there from 21 to 28 August 1807, and that each received a

daily ration of "1 ½ pounds of bread, 1 pound of meat, vegetables and

beer..." The French withdrew from Berlin in early

December 1808, and Prussian troops returned to the city on 10 December.

Although social and military reforms were introduced, it became clear

that the King and nobles no longer held absolute control. As one

example, Major Schill, commander of the 2nd Brandenburger-Hussars

Regiment, assembled his four batallions and "Jager" (mounted light

infantry) detachment at Tempelhof Field on 28 April 1809, then deserted

Prussia to fight against Napoleon. Letters were exchanged between

Napoleon and Frederick, who issued a proclamation: "On orders of His

Majesty, the King of Prussia, Our Gracious Lord, all are herewith most

earnestly warned not to make themselves guilty of similar actions..."

Shortly afterwards, on 31 May 1809, Danish and Dutch troops cornered

Schill’s Regiment near Stralsmund and annihilated them.

Prussia was coerced into signing another alliance with France

on 24 February 1812. Under its terms, the last remnant of the Prussian

Army - about 20,000 men - were to accompany Napoleon into Russia. It

also stipulated that Berlin would be re-occupied, and French troops

returned to the city on 24 February 1812. However,

the Berliners were not as calm as they outwardly appeared. A popular

movement was gaining acceptance among students and the middle class.

Jahn and Friesen had founded the German League, which sought to

overthrow French control. A turning point was reached when General Hans

Yorck von Wartemburg signed a separate treaty with the Russians at

Tauroggen on 30 December 1812, and removed the Prussians from the Grand

Army. Although the King In Berlin was dismayed by these events, he did

not issue a general call to arms. Instead, he left Berlin and went to

Breslau. After his departure, and while the city was

still under a French Garrison, the Berliners started to build a corps of

volunteers. The numbers were sufficient to give the garrison commander

cause for concern, for his 10,000 to 20,000 man garrison could

accomplish little against a popular uprising of up to 150,000. On

February 3rd, the King very reluctantly issued a call to arms, but this

was not against Napoleon, instead, "in defense of national interests".

On 20 February 1815, a small force of about 150 Russians dashed into

Berlin, and part of the population rose to support them. Of itself, this

did not seriously endanger French control of the city, but it was

additional cause for concern. When he was informed that the Russian main

body was marching on Berlin, the garrison commander, Eugen Beauharnais,

Vice-Regent of Italy, led his 20,000-man garrison through Hallesches Tor,

across Tempelhof Field, and out of Berlin. Prüssian and allied forces

moved in behind and prepared for Napoleon’s counter- attack.

Additional fortifications were hastily

erected, with redoubts added to the Kreuzberg, in the Hasenheide, and along the

Rollberge. Roughly 16 earthworks were built, spaced along the length of the

Landwehr Canal. Magazines were established and guns were mounted. The initial

French thrust was blunted at the Battle of Luckau on 4 June. A truce followed,

but Frederick proved to be less pliable than previously, and negotiations

failed. Napoleon then ordered a three-pronged attack on the city. Dudinot left

Bayreuth with 68,000 men and moved up from the South. A French army of 12,000

left Magdeburg and moved east, while Davoust led 40,000 men down from Hamburg.

The fortifications on Tempelhof Field were never tested. The

French were stopped cold at Gross-Beeren on 25 August. This was followed

by a second defeat for the French at Dennewitz, and then finally, there

was the major confrontation at Leipzig. Prussia gained in the resultant

peace treaty. However, Frederick Wilhelm III proved to be less than

grateful, for he sternly repressed the movement that had saved his

throne. Reforms had been introduced and – as always -

the Prussian Army was hard at work on Tempelhof Field. Activities by

this time lasted so long and involved so many troops, that the Tempelhof

Farmers were again experiencing serious financial difficulties. The

issue had been raised in the 18th century and now it was brought up

again. A bitter "legal" battle started in 1817, when Colonel von Krohn

was apportioned a permanent training area south of the"Privat-Weinberge",

in the area now occupied by theTraffic Police, across from Headbuilding

East, on Tempelhof Field. The Prussian State Treasury finally purchased

the field in 1826/27, and reportedly paid 30 to 49 Taler per Morgen

(0.6-0.9 Acres), causing a "Gold Rush" atmosphere among the farmers of

Tempelhof. The military now had permanent but not

sole use of Tempelhof Field. Unlike the troops, the Berliners who came

here, did so voluntarily and in great numbers. It became a favored spot

for family and recreational activities of all types. Friedrich Ludwig

Jahn, who is also known as "Father Jahn", founded Germany’s first public

physical fitness training area there in 1811. This fitness facility,

which was located in the northeast corner of the Hasenheide, attracted

large numbers of health enthusiasts. Coffee houses, beer halls and

open-air cafes appeared along the fringes of the field. Tempelhof

tourism received a major boost in 1821 when the National Monument to the

Wars of Liberation (1815—1815) was unveiled atop Tempelhofer Berg, which

was then renamed the "Kreuzberg". This was the highest of the five "Weinberge"

on the north side of the field. It soon collected a steady clientele for

its cafes and restaurants. The "Verein für

Pferdezucht und Pferdedresseur" (Association for Horse-Breeders and

Horse-Trainers) promoted horse races on the western part of the field

starting in 1830. A racetrack was constructed in 1835, but operations

were forced to move in l840, when tracks for the Berlin-Anhalt Railway

were laid through there. Horseracing then moved to a track in the

southeast section of the field, where it continued until 1867, and drew

high society to Tempelhof. At the other end of the social spectrum, "Ma

Kreideweiss", the proprietress of the local "Gasthaus", achieved

international recognition, for a postcard mailed in Graz and addressed

simply to "Julius Kreideweiss in Europe", was promptly and correctly

delivered. This card was on display in the Tempelhof Local History

Museum). The big race took place every year at the time that the "Wollmarkt"

(Wool Fair) was held. "Iron Horses" also ran at least

one race across Tempelhof, on 24 July 1841. This was the day when Borsig

proved the worth of his steam engine by defeating a Stephenson (English)

engine in a race. The starting point was the Anhalter Bahnhof and the

finish line was at Juterbog - these points were connected by the single

track of the Anhalter Railway. Borsig’s machine was ten minutes faster

and thus he broke the sales monopoly previously held by the Americans

and English for the developing German railways.

Military drills, exercises, reviews and parades remained a standing

attraction, and some of these were very large and extravagant. The

evolutions now included the new military technology branches of combat

engineers and trainmen. This was

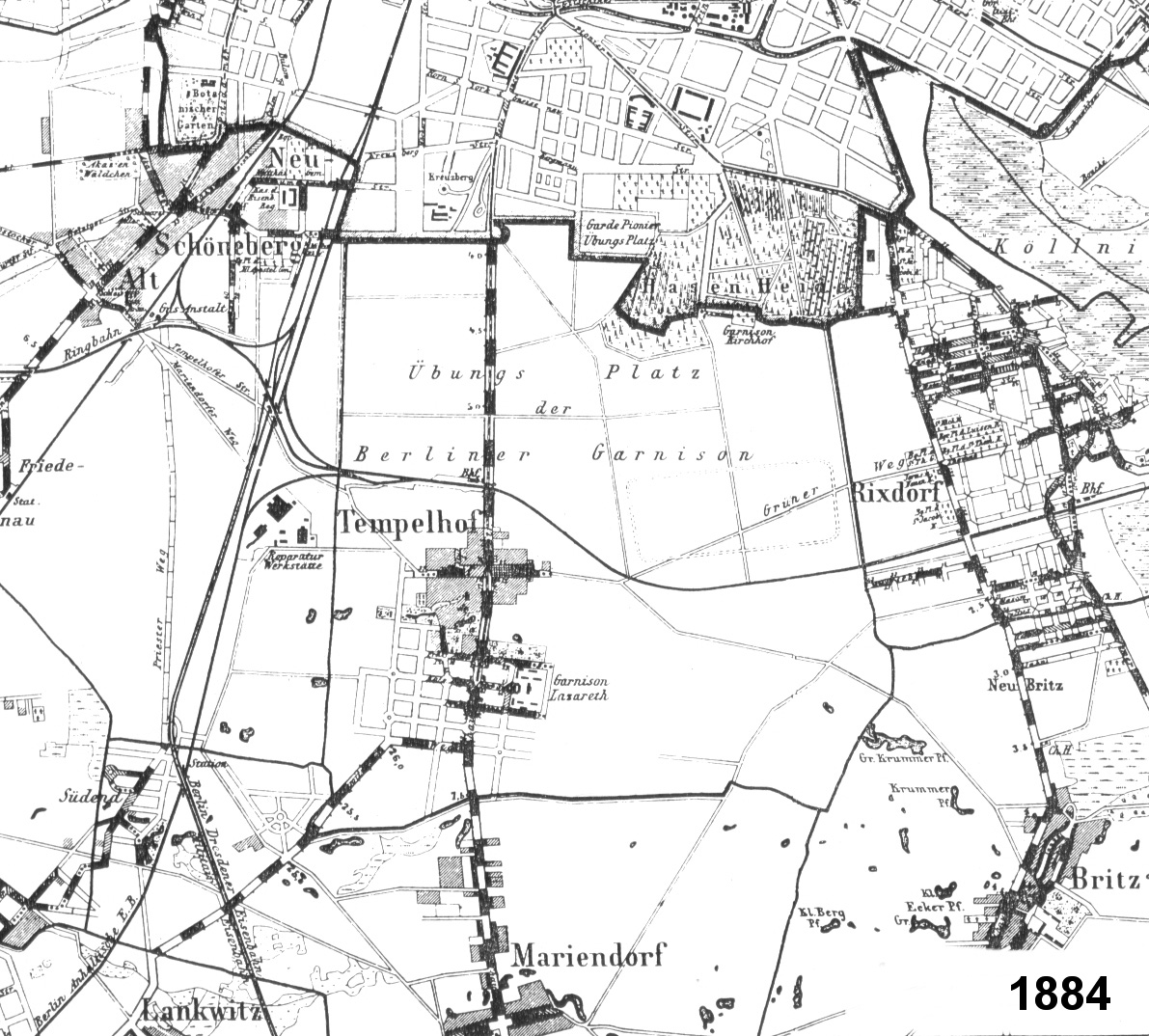

the period of the industrial revolution. By 1850, manufactured goods governed

the consumer market. These were cheaper and more plentiful than hand-crafted

items, so many small craftsmen were forced out of business. But factories

required manpower, starting a major shift in population into cities. The

population of greater Berlin grew from 157,000 in 1813 to 548,000 by 1861.

Housing became a critical issue and it was answered by construction of hastily

built high-rise stacks of small apartments called "Mietskasernen"

(Rental-Barracks) by the Berliners. Tempelhof Field’s status as a maneuver

terrain saved it from being completely overrun by the brick jungle. However, the

north boundary was rolled back to its present day location, and chunks were

taken out of the rest of the perimeter. The Napoleonic Wars

officially terminated the First German Reich. The Treaty of Tilsit